Source: How This Happened – Demystifying the Nile: History and Events Leading to the Realization of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Author: Dereje Befekadu Tessema

—

Introduction

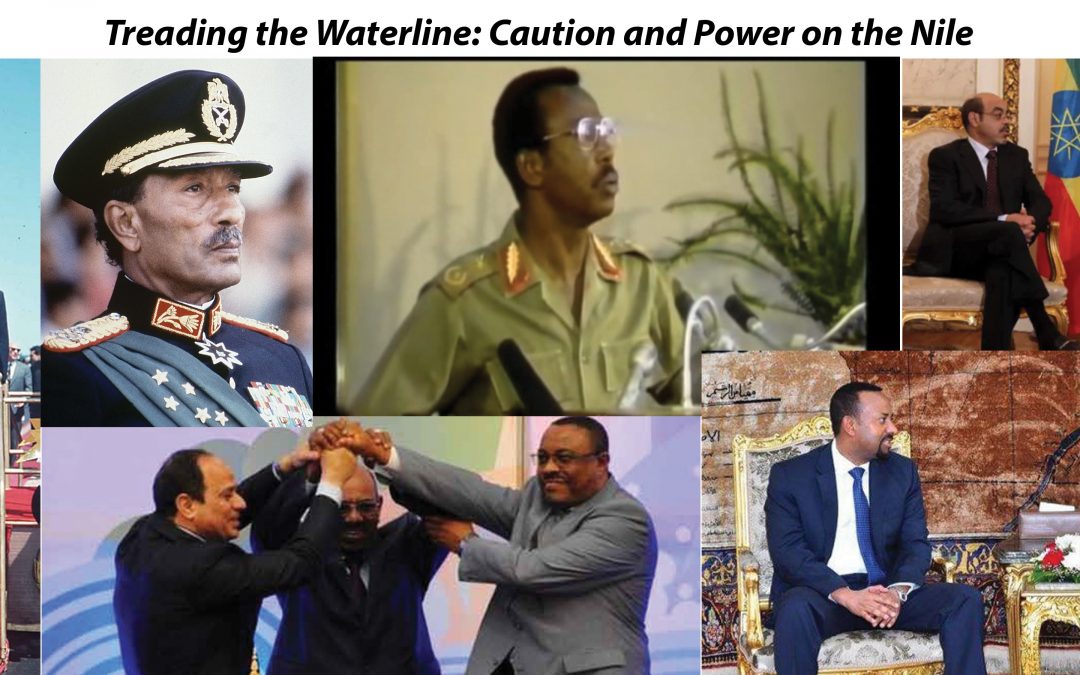

This Installment spans five decades during which the Nile’s politics were shaped as much by caution and national interest as by rivalry. From Haile Selassie to Meles Zenawi and from Nasser to Sisi, leaders in Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan navigated coups, wars, famines, and shifting superpower alignments—while working to protect water security at home.

Rather than a simple winner–loser story, the record shows alternating cycles of tension and restraint: Ethiopia’s revolution and protracted civil conflicts, Egypt’s post-Aswan development and regional realignments, Sudan’s internal struggles, and periodic diplomatic openings. Milestones such as the 1993 Ethiopia–Egypt framework, the launch of the Nile Basin Initiative (1999), and upstream cooperation efforts in the 2000s reveal how statecraft kept channels open even when positions hardened.

What you’ll read in Installment #3

- How Cold War and post-Cold War dynamics reframed water, security, and development across the basin.

- Why leaders on all sides balanced assertive rhetoric with pragmatic, interest-based diplomacy.

- The policy through-lines that set the stage for the 2010s, when debates over cooperation, sovereignty, and development intensified.

—

The period from 1960 to 2010 represents one of the most dramatic transformations in the history of Nile River politics. These five decades witnessed Ethiopia’s remarkable evolution from a marginalized observer, whose water development projects could be blocked by foreign powers, to the driving force behind the most significant multilateral cooperation framework in the basin’s modern history. This transformation occurred against the backdrop of the Cold War, decolonization, regime changes, devastating famines, and shifting global power dynamics that would ultimately reshape the entire geopolitical landscape of the Nile basin.

This era was built upon the dramatic changes of the preceding 159 years (1800-1959), when the Nile evolved from an ancient waterway governed by traditional diplomatic arrangements into a tool of imperial expansion and Cold War competition. The Mohammed Ali dynasty’s failed attempts to control Ethiopia through military conquest, culminating in the defeats at Gundet (1875) and Gura (1876), had established that Ethiopia could not be subdued by force. British imperial consolidation through the “Veiled Protectorate” and the 1929 Nile Waters Agreement had created a system of downstream control that excluded upstream countries from decision-making. The 1957-1964 U.S. Blue Nile Development Study identified the “Border Dam” location, which would later become the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Meanwhile, the 1959 Egypt-Sudan agreement formalized downstream monopoly over Nile waters, with explicit provisions to “defend the coalition against any request by the other riparian countries.”

The story of these fifty years reveals how patient diplomacy, strategic learning, demographic pressures, and changing international circumstances converged to enable Ethiopia—the source of 80% of the Nile’s waters—to finally assert its rightful place in determining the river’s future. From the mysterious circumstances surrounding the 1960 failed coup, which may have prevented Soviet financing of Ethiopian development, to the signing of the Cooperative Framework Agreement in 2010, which legitimized the rights of upstream countries, this period laid the foundation for Ethiopia’s bold decision to construct the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

The 1960 Ethiopian Coup: Cold War Politics and Water Rights

The decade began with an event that would cast a long shadow over Ethiopian politics and reveal the extent to which global powers would intervene to control Nile waters. In 1959, Emperor Haile Selassie achieved a remarkable milestone: securing a $100 million loan from the Soviet Union—the most significant amount the USSR had ever promised to any African country. This loan was intended to support Ethiopia’s five-year development plan, following the refusal of Western nations to similar requests. The irony was stark: the source of 80% of the Nile’s waters could not secure financing from the West for development projects, while downstream Egypt received massive support for the Aswan High Dam.

However, of the promised Soviet funds, only $12 million was ever delivered, primarily for an oil refinery at the port of Assab. In December 1960, while Emperor Haile Selassie was on a state visit to Brazil, his imperial bodyguard and several military officers attempted a coup that lasted four days but left permanent scars on the country. For fifty years, this event was understood as a typical palace coup driven by internal grievances.

The timing and context of this coup attempt must be understood in relation to the broader Cold War competition over the Nile Basin. The U.S. withdrawal of support for Egypt’s Aswan High Dam in 1956, followed by Soviet financing of the project, had demonstrated the strategic importance of Nile infrastructure in superpower rivalry. Emperor Haile Selassie’s 1959 visit to Moscow, where he received both the loan commitment and an honorary degree for “strengthening peace and the Bandung principles of peaceful coexistence,” alarmed Western powers already concerned about losing another strategic Red Sea location to Soviet influence after Egypt’s drift toward the USSR.

The publication of new evidence in 2012 fundamentally challenged this narrative. Dejazmach Wolde Semaiat Gebrewold’s memoir revealed conversations with British officers who had explicitly warned that Ethiopia would not be allowed to take “a dime” from the Soviet loan, and that the U.S. and UK would “fight to prevent the loan from happening.” Declassified U.S. documents from the Office of the Historian confirmed these suspicions, revealing Operation Plan for the Horn of Africa and extensive discussions about blocking Soviet influence in Ethiopia.

The circumstantial evidence is compelling: the U.S. ambassador was reportedly present at the Imperial Palace during the coup attempt, and the loan was never utilized despite the emperor’s survival and return to power. This suggests that the coup served its intended purpose as a warning rather than a genuine attempt at regime change. The timing—immediately after the U.S. had withdrawn support for Egypt’s Aswan Dam, leading to Soviet financing—suggests that preventing another strategic Red Sea country from falling under Soviet influence was a priority worth extreme measures.

The coup’s aftermath reveals the effectiveness of this pressure. Despite surviving the attempt, Emperor Haile Selassie’s government failed to develop a national policy for Blue Nile development, despite repeated appeals from his ministers. The momentum for major water development projects was lost, and Ethiopia remained relegated to the role of passive observer in Nile politics for another decade. This marked a stark contrast to the emperor’s earlier assertiveness, including his 1956 Communique and 1957 Aide Mémoires that had formally announced Ethiopia’s intention to develop the Blue Nile for irrigation and hydropower, declaring that “Ethiopia has the right and obligation to exploit its water resources for the benefit of present and future generations of its citizens.”

Egyptian Aggression and the Search for New Relationships (1970s-1980s)

The 1970s brought new leadership to Egypt and Ethiopia, setting the stage for a complex dance of confrontation and reconciliation that would shape bilateral relations for the next two decades. Anwar Sadat’s rise to power in Egypt marked a departure from Nasser’s policies in many areas, but continuity in one crucial respect: the determination to prevent Ethiopian development of the Nile waters.

Sadat’s approach was more explicitly aggressive than that of his predecessor. He openly supported Eritrean secession movements and Somali irredentism, viewing the weakening of the Ethiopian state as essential to maintaining Egyptian control over the Nile. This strategy culminated in his 1979 announcement of plans to divert Nile waters to the Sinai desert to establish irrigation for 35,000 Bedouins—a project that would have further reduced water flows to downstream countries while Egypt maintained its monopoly on Nile resources. This proposal exemplified the continuation of Egypt’s historical approach, from Mohammed Ali’s 19th-century military campaigns to control the Ethiopian highlands, through British imperial arrangements that granted Egypt exclusive rights, to modern attempts to expand usage while blocking upstream development.

Ethiopia’s response marked a crucial evolution in its diplomatic strategy. The 1980 memorandum to the Organization of African Unity opposing Sadat’s Sinai project represented the first formal assertion of Ethiopia’s rights as a source country under international water law. The memorandum presented three key arguments: as the source of the Nile, Ethiopia had every right to utilize the waters for its own development; diverting the river from its natural course violated international water law; and Egypt had refused to incorporate the interests of other riparian countries into its planning.

Egypt’s reaction was swift and threatening. Sadat not only threatened military action if Ethiopia made any move toward water development but also lobbied the Carter Administration to provide military assistance under the pretext that Ethiopia was preparing to invade Somalia. His statement that “We are not going to wait to die of thirst in Egypt. We’ll go to Ethiopia and die there” revealed the extent to which Egyptian leaders viewed any Ethiopian development as an existential threat.

The 1974 revolution that brought Mengistu Hailemariam and the Derg to power created new geopolitical dynamics. While Ethiopia moved toward the Soviet bloc, Egypt under Sadat shifted toward the West, creating a complex quadrilateral relationship involving the superpowers. The Ethiopian government, faced with Egyptian-supported insurgencies and threats, established a committee of 15 senior diplomats to investigate Egyptian activities and recommend responses, including the possibility of severing diplomatic relations.

Mubarak’s Diplomatic Revolution and Ethiopia’s Policy Development

The assassination of Sadat in 1981 brought Hosni Mubarak to power and marked a fundamental shift in Egyptian strategy toward Ethiopia. Unlike his predecessors, Mubarak recognized Ethiopia’s growing regional influence and the counterproductive nature of confrontational policies. Between 1981 and 1985, Egypt sent over 59 partnership invitations to Ethiopia for joint projects in agriculture, communications, engineering, and education.

This diplomatic offensive reflected a sophisticated understanding of changing regional dynamics. During Mubarak’s 1986 visit to Addis Ababa for the OAU summit, he explicitly acknowledged that Sadat’s support for Somalia during the 1977-78 war had been a “mistake”. He requested that Somalia recognize the Ogaden as part of Ethiopia. His statement, “I do not wish to lose Ethiopia to gain Eritrea,” represented a fundamental recalibration of Egyptian priorities.

The success of this approach was evident in Mengistu’s 1987 visit to Egypt—the first by an Ethiopian leader in decades—which resulted in the creation of the Joint Ministerial Economic Commission. However, this diplomatic warming occurred alongside Ethiopia’s systematic development of a national water policy that would provide the intellectual foundation for all subsequent negotiations.

The Mengistu government’s approach to the Nile issue represented a significant departure from the ad hoc responses of previous administrations. After an extensive study of various legal doctrines—from the Harmon Doctrine, which asserts absolute upstream rights to principles of equitable and reasonable use—Ethiopia articulated a policy of honoring the 1902 agreement not to divert the whole flow, while claiming the right to use water for national development based on international law.

This policy framework, presented by Mengistu to Mubarak in 1987, became the foundation for Ethiopia’s subsequent positions in all multilateral negotiations. The policy struck a balance between respecting downstream concerns and asserting upstream rights, providing a defensible legal and moral foundation for Ethiopian development projects.

The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities: Famines and Blocked Development

The irony of Ethiopia’s position in the Nile basin became most apparent during the devastating famines of 1972-74 and 1982-86. These disasters, which killed millions and affected eleven million people, occurred in a country that is the source of most of the Nile’s water and provides 4 billion cubic meters of fertile soil annually to downstream countries. As one analysis noted, if Ethiopia had utilized its rivers and tributaries for development purposes—building dams for power generation and irrigation systems to enhance agricultural productivity—the country would have had better resilience against drought.

The Tana-Beles Project, designed in response to the 1983-85 famine that resulted in the deaths of 1.2 million people, exemplified the challenges Ethiopia faced. This project proposed diverting water from Lake Tana to the Beles River to resettle 200,000 farmers and reduce dependence on rainfall. However, in 1990, Egypt successfully lobbied the African Development Bank to deny financing for the program, demonstrating how downstream hegemony could prevent upstream development even in humanitarian crises.

The international community’s response to these famines—massive humanitarian aid to address symptoms while blocking development projects that could address root causes—revealed the structural inequities in Nile basin politics established during the imperial era. Countries that regularly experience droughts, such as the United States and Australia, have developed resilience infrastructure that minimizes the impacts of droughts. Ethiopia, despite being the source of the Nile, was prevented from building similar infrastructure and forced to rely on emergency aid during cyclical crises. This situation echoed the historical pattern identified by Lord Salisbury in the 19th century: whoever controlled the Ethiopian highlands could “flood the Valley of the Nile or make of it a blistering desert at will”—yet Ethiopia itself was denied the benefits of this geographic advantage.

The EPRDF Era and Strategic Recalibration (1991-1999)

The 1991 collapse of the Mengistu government and the rise of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) created both opportunities and challenges for Ethiopian water policy. The new government, initially supported by the United States, Egypt, and Sudan during its struggle against the Derg, faced expectations that it would abandon previous water development ambitions in favor of maintaining good relationships with these supporters.

Indeed, sources indicate that the U.S. government sent strong communications to the Ethiopian government that it would not support any Nile River project that could negatively impact Egyptian water supplies. Most mega-projects from the previous government, including the Tana-Beles project, were put on hold, leading to speculation about whether this represented resource constraints, political priorities, or external pressure.

The 1993 Framework for General Cooperation between Ethiopia and Egypt, a controversial document, exemplified the challenges facing the new government. Article 6 of this agreement appears to grant Egypt veto power over Ethiopian Nile projects, stating that both parties will “consult and cooperate in projects that are mutually advantageous.” This language was widely viewed as heavily favoring Egypt, raising questions about the new government’s commitment to Ethiopian water rights.

However, the EPRDF’s most significant contribution was transforming Ethiopia’s approach from passive observation to active engagement in regional water politics. Unlike previous governments that had declined invitations or participated only as observers, the new leadership decided to engage directly with multilateral initiatives, viewing these platforms as opportunities to share Ethiopia’s development plans with riparian countries, donors, and the international community.

The Diplomatic Revolution: From Observer to Driver

Ethiopia’s participation in the “Nile 2002” conference series, initiated by Egypt, marked a watershed in regional water diplomacy. At the first conference in Aswan in 1993, Ethiopia announced its intention to utilize Nile waters through a national white paper to achieve “food self-sufficiency goals.” This paper clearly underscored Ethiopia’s determination to use Nile waters for national development.

By the fourth conference in Kampala in 1996, the agenda had shifted from technical discussions to debates about equitable utilization among riparian countries. This change indicated a broader consensus among upstream countries in support of equitable water sharing, despite Egyptian efforts to maintain a focus on technical cooperation that preserved the status quo.

The 1997 Addis Ababa conference, with over 400 participants from 20 countries, saw Ethiopia deliver what many considered its “first firm stand.” The Ethiopian white paper stated that past and current Nile utilization favored Sudan and Egypt, and that maintaining this status quo could trigger unilateral actions by riparian countries. This warning proved prescient, foreshadowing the eventual construction of the GERD.

Ethiopia’s most significant diplomatic achievement during this period was proposing “Project D3″—the formation of the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework through a Panel of Experts with three representatives from each riparian country. This proposal, accepted by the Nile Council of Ministers, provided the mechanism through which Ethiopia could advance its agenda within a multilateral framework rather than through bilateral negotiations with Egypt, where the power imbalance was decisive.

The Birth of Multilateral Cooperation: NBI and CFA

The establishment of the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) in 1999 represented the culmination of Ethiopia’s patient diplomatic strategy. The NBI’s shared vision—”to achieve sustainable socio-economic development through equitable utilization of, and benefit from, the common Nile basin water resources”—embodied principles that Ethiopia had been advocating for decades.

The NBI’s structure reflected lessons learned from previous failed initiatives. Unlike earlier Egyptian-dominated partnerships, such as Undugu and TECCONILE, the NBI established genuinely multilateral institutions with a secretariat in Uganda, an Eastern Nile Technical Regional Office in Ethiopia, and equal representation for all member countries.

The organization’s three core functions—facilitating basin cooperation, managing water resources, and developing water resources—provided frameworks for advancing Ethiopian interests through legitimate multilateral processes, rather than confrontational bilateral negotiations.

The NBI’s 2017-2027 strategy articulated goals that directly addressed Ethiopia’s development needs, including water security to meet rising demand, energy security through hydropower development, food security through enhanced agricultural productivity, environmental sustainability, climate change adaptation, and strengthened transboundary governance. These goals provided international legitimacy for the types of projects Ethiopia had long sought to implement.

Technical Preparation and Strategic Patience

Parallel to these diplomatic efforts, Ethiopia systematically built the technical foundation for water development through comprehensive studies of its river basins. The 1999 Abbay River Basin Integrated Development Master Plan represented the first comprehensive analysis since the 1960s U.S. reconnaissance work that had identified the “Border Dam” location.

Coordinated by the Ministry of Water Resources and involving international consultants, including French companies BCEOM and BRGM, this master plan validated Ethiopia’s immense hydropower potential. It provided detailed technical justification for major development projects. Notably, this study built upon and validated the earlier 1957-1964 U.S. Blue Nile Development Study, which had identified 33 interconnected projects, including the “Border Dam” that would later become GERD. The completion of this comprehensive analysis coincided with the establishment of the NBI, demonstrating how Ethiopia had prepared both the technical and diplomatic groundwork for asserting its water rights.

The Cooperative Framework Agreement: Legitimizing Upstream Rights

The signing of the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) on May 14, 2010, in Entebbe, Uganda, marked a historic milestone in Nile Basin politics. After thirteen years of negotiations through the Panel of Experts established in 1997, six upstream countries (Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, and Burundi) signed an agreement that fundamentally challenged the colonial-era treaties that had given Egypt exclusive rights to Nile waters.

The CFA’s significance extended beyond its specific provisions to its establishment of a new principle: that all riparian countries have rights to the waters of an international river system. By providing a legal framework for equitable utilization and challenging Egypt’s veto power over upstream development, the CFA laid the foundation upon which Ethiopia could proceed legitimately with major water projects.

The timing of the CFA signing proved fortuitous, coinciding with the Arab Spring that began in late 2010 and early 2011. As Egypt became consumed with internal political upheaval following Mubarak’s fall, Ethiopia found itself with unprecedented freedom of action to pursue its long-delayed development agenda.

In Summary: The Foundation for Modern Nile Politics

The fifty-year period from 1960 to 2010 transformed Ethiopia from a marginalized observer whose development could be blocked by foreign powers to the central player in Nile basin politics. This transformation resulted from a combination of strategic patience, diplomatic learning, technical preparation, and changing international circumstances that gradually eroded the imperial-era arrangements that had excluded upstream countries from decision-making.

The journey represents a remarkable reversal of the power dynamics established during the 159 years of imperial competition (1800-1959). Where Mohammed Ali’s military campaigns had failed to subjugate Ethiopia through force, and British imperial arrangements had succeeded in marginalizing Ethiopian interests through diplomatic isolation, the post-1960 period demonstrated how patient multilateral engagement could gradually shift the balance of power back toward the geographic source of the river’s waters.

The journey from the 1960 coup, which may have been orchestrated to thwart Soviet financing for Ethiopian development, to the signing of the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) in 2010, illustrates how Ethiopia carefully established the moral, legal, and technical foundation necessary to assert its water rights. The patient work of building multilateral institutions, developing technical capacity, and articulating legal principles provided the foundation for Ethiopia’s 2011 announcement that it would construct the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

The period established several crucial precedents that continue to shape contemporary Nile politics: the principle that upstream countries have legitimate development rights, the importance of multilateral rather than bilateral negotiations, the role of international law in resolving water disputes, and the recognition that demographic and development pressures make upstream water use inevitable. These principles directly challenged the colonial-era framework embodied in the 1929 and 1959 agreements that had treated the Nile as an exclusively downstream resource.

Most importantly, these five decades demonstrated that while downstream countries could delay upstream development through political pressure and financial manipulation—as evidenced by the blocked Soviet loan in 1960 and the African Development Bank’s refusal to finance the Tana-Beles Project in 1990—they could not prevent it indefinitely. Ethiopia’s patient accumulation of diplomatic legitimacy, technical capacity, and international support created the conditions for the dramatic assertion of upstream rights that would transform Nile politics in the following decade. The stage was set for the most significant challenge to downstream hegemony in the modern history of the Nile River, building upon foundations laid during both the imperial transformation period (1800-1959) and the Cold War crucible (1960-2010).